by Nathan Bernacki

[PDF View]

There is a specific set of criteria professionally-trained folk musicians use to differentiate meters in a contemporary Bulgarian context: sub-division, beat, and tempo. My field experiences in Bulgaria have shown me that these terms are generally understood, but sometimes in more implicit ways (e.g preference for demonstrative over verbal communication of meter). Thus, the adoption of these terms is for the convenience of communication within the scholarly discourse on metric theory, especially that of Justin London (2012). Regional characteristics from the six ethnographic regions of Bulgaria also affect these criteria, and should also be considered when analyzing meter. I will now briefly discuss each of these points, contextualized in the history of meter as conceived of by folk musicians.

The subdivision level is a relatively new addition to Bulgarian metric thought, as meters before 1944 were never described through the enumeration of subdivisions by folk musicians. This was a consequence of the institutionalization of Bulgarian folk music, and this method of describing Bulgarian meters still remains (Rice 1994; Buchanan 2006). Contemporary professionally-trained folk musicians describe ‘short’ and ‘long’ beats as consisting of two and three subdivisions respectively.1 References to subdivisions can be seen in the notation of folk orchestra arrangements (in time signatures), and musicians will explain how a Kopanitsa (11/8, 2+2+3+2+2, moderate-fast) will have five main beats with eleven subdivisions.

The beat level is defined by melodic accentuation, implicit melodic and rhythmic rules, grouping, and most importantly, dance steps. Bulgarian folk dances do not step to the subdivision level, however, only at the beginning of each subdivision grouping. For example, if a solo instrumental performance of a Ruchenitsa (7/8, 2+2+3, moderate-fast) was performed devoid of any melodic accents, one could distinguish it from a Chetvorno (7/8, 3+2+2, moderate-fast) by observation of when dancers step. Similarly, the beginning of each cycle can be determined by when the dance begins.

Tempo, as described by Rice, “is the only element of musical time discussed explicitly by Bulgarian singers. They compare performances along a scale from slow (bavno) to fast (burzo),” (Rice 1980:62). A 7/8 (3+2+2) at a slow tempo (e.g. Shirto) is a different dance than a 7/8 (3+2+2) at a faster tempo (e.g. Ginka), with these distinctions exemplified by the variety of dance names, dance steps, and implicit melodic and rhythmic tendencies. I am deliberately not defining slow, or moderate-fast, because these tempo markings would overlap as different ethnographic regions have different tempo-related standards.

Regional characteristics are metrically salient as well, such as a metric phenomenon unique to the Pirin-Macedonia region that I have termed “beat stretching”. This phenomenon emerges when the timing of beats within a meter do not align with a 2:3 proportion. The reason for using isochrony as a baseline for comparison is that it is a quality that dominates most dance music in Bulgaria, even within the Pirin-Macedonia region. Also many dances that start with stretched beats progressively change to an isochronous feeling midway through the performance (e.g. Makedonsko Horo).

An isochronous vs. non-isochronous dichotomy is not an emic categorization of meter. Bulgarian musicology going back more than a century, has catalogued meters by their number of subdivisions (even though folk musicians in the early 20th century did not conceive of meter as such). However, modern-day performers have adopted this categorization method as well, and do recognize a subdivision level. In light of this method, I will now provide an example of this emic conception of meter in the context of 7-subdivision meters.

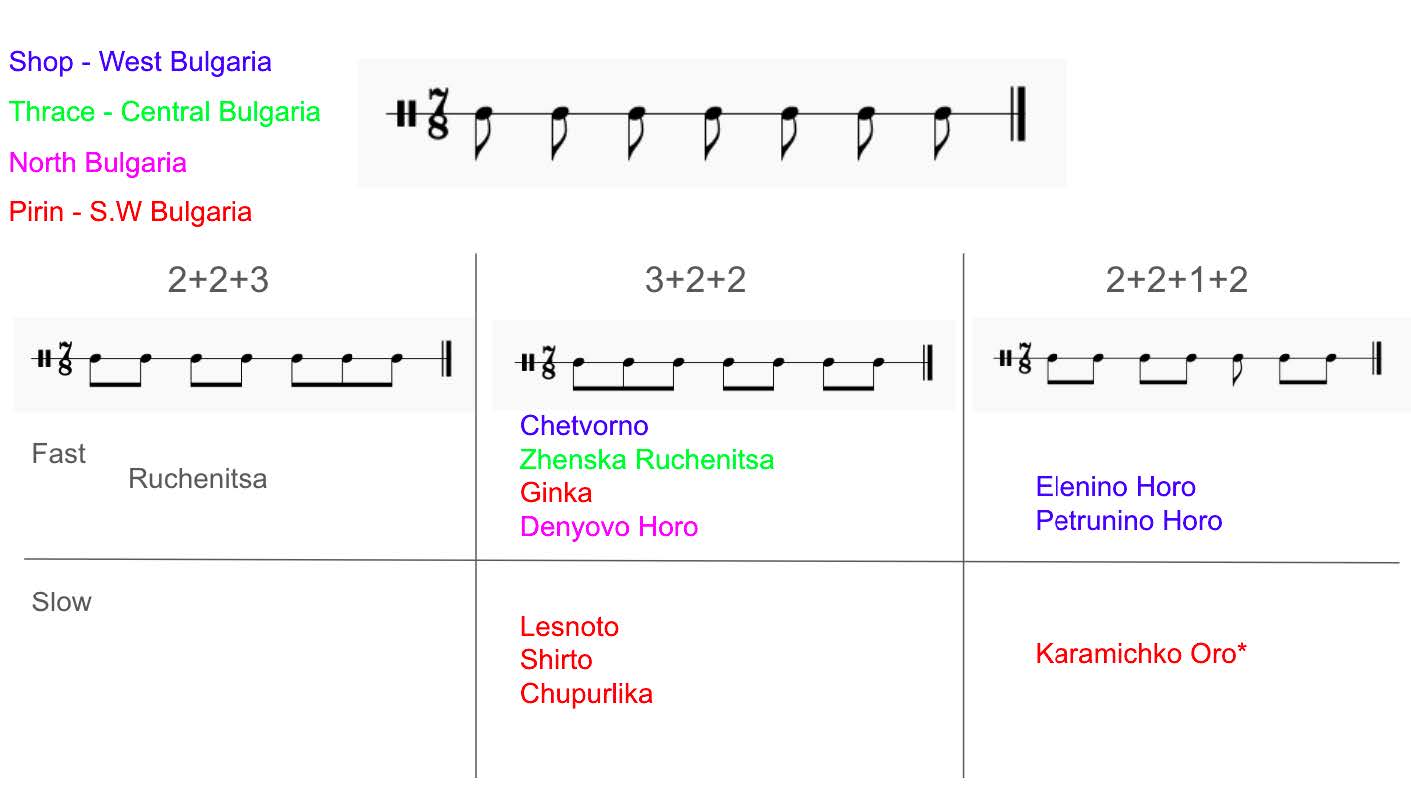

7-subdivision meters organised by grouping and tempo.

Above is a graph dividing the various 7-subdivision meters by their subdivision and tempo.2 Ruchenitsa is grey because it is found in all ethnographic regions of Bulgaria, and Karamichko Oro has an asterisk because it is found more often in Serbia and Macedonia. Even though Ginka, Denyovo Horo, Zhenska Ruchenitsa, and Chetvorno Horo are from different ethnographic regions and have different characteristic dance steps, the subdivision, number of subdivisions, relative tempo, and when the dancers step are the same, and all allow the same implicit rhythmic possibilities.

Contextualized in the broader discourse of cycles, the durational and rhythmic processes of most meters in Bulgarian folk dance music resemble those in ‘grooves’ of popular music, as their duration falls within the span of the perceptual present. These short cycles are the primary method of temporal organisation in Bulgarian folk dance music.3 Other types of cycles such as non-metric cycles and cycles whose durations exceed the perceptual present can be found mainly in vocal music that does not feature a choreographic dimension, such as Shop diaphonic singing (e.g. Tri Mi Zvezdi). In this tradition, musicians make timing judgments through syllabic accentuation, shared expectations of the syllabic structure of Bulgarian folk poetry, familiarity with their partner’s singing style, and perhaps breath length.

Footnotes

1 Contemporary professionally-trained folk dancers also acknowledge this subdivision level, also as a consequence of state-sponsored folklore ensembles.

2 The rightmost column of a 2+2+1+2 subdivision does not conform to London’s Metric Well-Formedness Rules (London 2012). For an in-depth discussion of this grouping see Goldberg’s What’s the Meter of Elenino Horo? (2019).

3 Musicians do not describe meter with the term ‘cycle’, but for the sake of discourse these meters can be described as cycles. The Bulgarian word for meter is размер (razmer).

Works Cited

Buchanan, Donna. 2006. Performing Democracy: Bulgarian Musicians in Transition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goldberg, Daniel. 2019. What’s the Meter of Elenino Horo? Analytical Approaches to World Music. Vol. 7, Issue 2, Pages 69–107.

London, Justin. 2012. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rice, Timothy. 1980. Bulgarian Musical Thought. Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council, Vol. 12, pp. 43-66.

——— 1994. May it Fill Your Soul. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.